The challenges we are facing

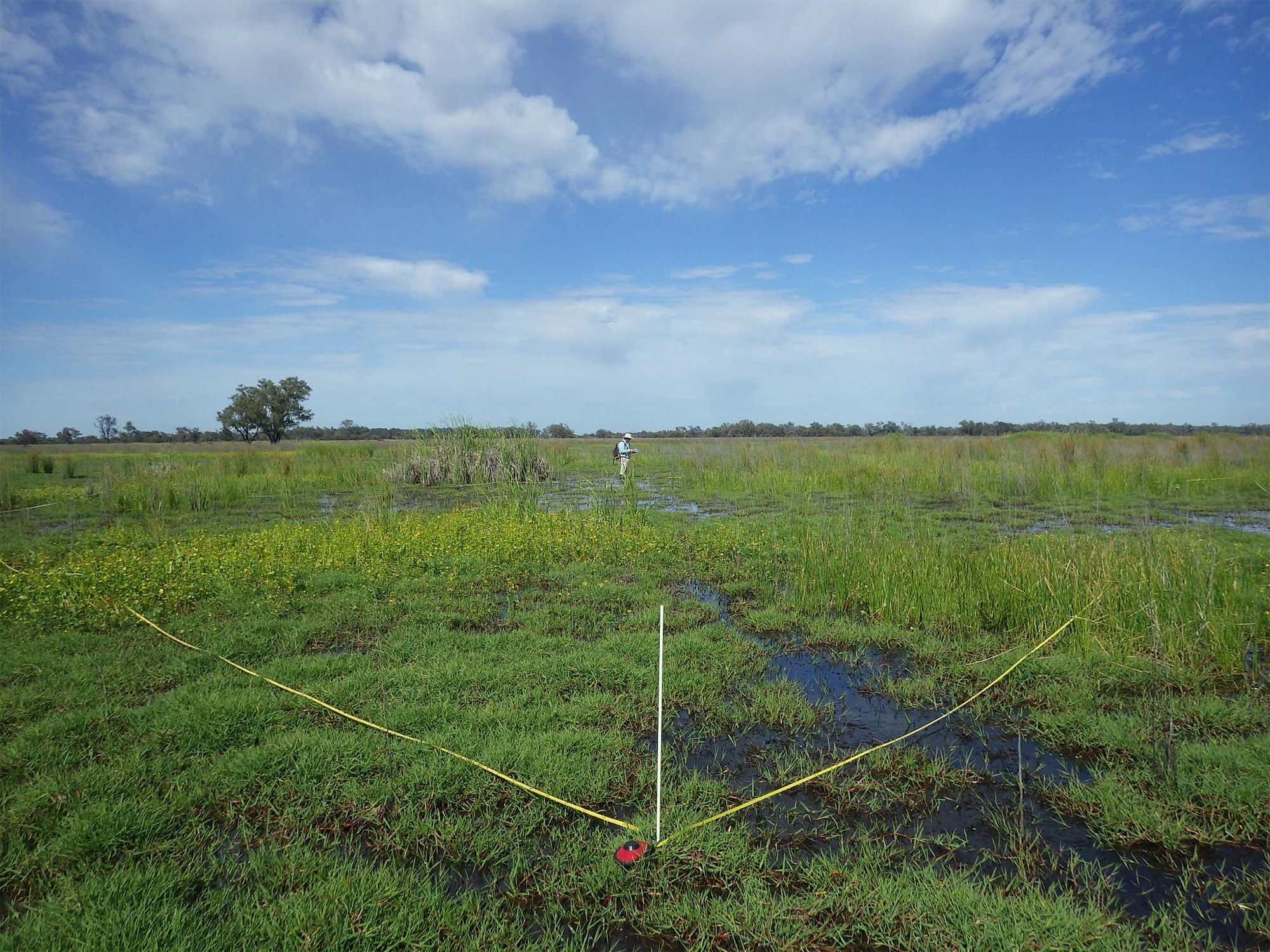

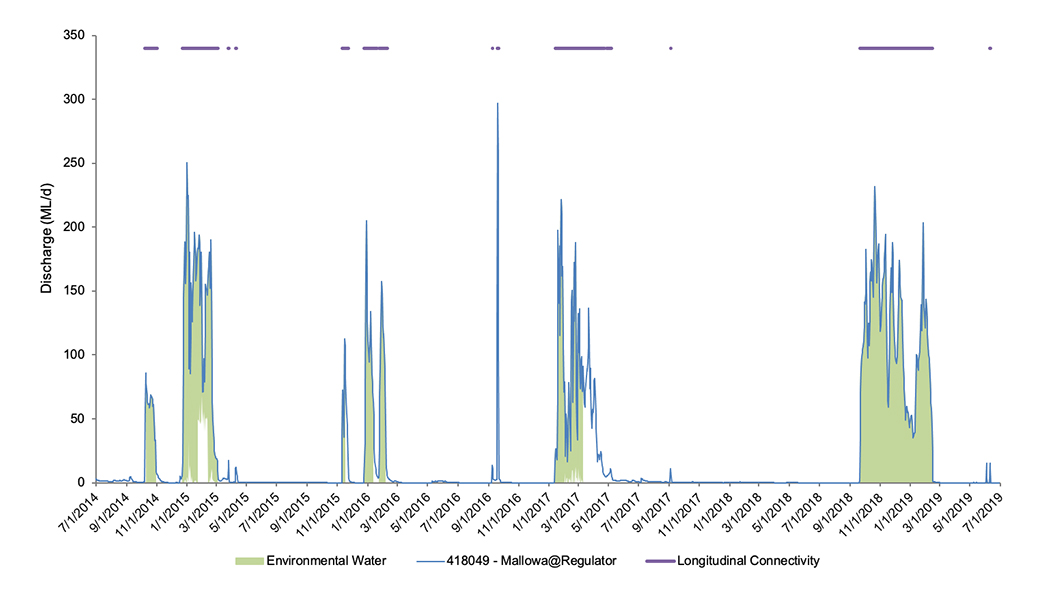

As a result of extensive clearing for agricultural development, vegetation communities on the floodplains in the Gwydir are highly fragmented (broken up) and in poor condition. Since the regulation of the Gwydir River in the 1970’s (construction of Copeton Dam and management of water), the extent and condition of semi-permanent wetland and floodplain vegetation communities have declined. Less frequent inundation of the floodplain as a result of regulation has reduced floodplain pasture productivity and influenced changes in land use from grazing to cropping.

These changes means that the Gwydir now has a number of Endangered Ecological Communities and Threatened Ecological Communities. This has a flow on effect as vegetation provides habitat for waterbirds, reptiles, frogs, woodland birds and terrestrial species such as the Eastern Grey Kangaroo. Floodplain wetlands and waterholes, in-channel lagoons, sedgelands, cumbungi stands, lignum, belah, coolabah and river red gums are key vegetation communities that make up key waterbird breeding habitat.

Aquatic ecological communities are also in poor condition, with a decline in native fish populations and species such as the Murray cod, Golden perch, Silver perch, Purple spotted-gudgeon and Eel-tailed catfish, of concern. Threatening processes to aquatic ecological communities in the Gwydir Wetlands include:

- installation and operation of in-stream structures that change natural flow patterns of rivers and streams (dams and weirs)

- the removal of large woody habitat which provides in-stream habitat for fish and invertebrates

- the degradation of native riparian vegetation (vegetation that borders waterbodies) due to clearing, grazing, spray drift and changes in flow patterns

- the introduction of native and introduced (Carp, Goldfish and Gambusia) freshwater fish to new areas of the river catchment which is outside their natural range. This creates more competition for resources and increases predation of other native fish species