Ecosystem Diversity

Water is the lifeblood of the Murray-Darling Basin, it courses through rivers and streams from the headwaters in southern Queensland and the eastern highlands, to the estuary and river mouth in South Australia. Along the way rivers and streams replenish a rich array of lakes, wetlands and floodplain ecosystems.

Over the past 9 years, the Ecosystem Diversity Theme has worked to quantify the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water to protecting and restoring these water-dependent ecosystems in the Basin.

Image: Intersection of ecosystem and environmental water mapping along the Murray River upstream of Robinvale. Creator: Shane Brooks

Introduction

The Murray-Darling Basin is a rich tapestry of water-dependent ecosystems that includes rivers, streams, billabongs, lakes, wetlands, floodplains and an estuary. These water-dependent ecosystems provide vital habitats for a wide range of plant and animal species.

The Ecosystem Diversity Theme estimates how Commonwealth environmental water contributes to protecting and restoring water-dependent ecosystems in the Basin. The work undertaken has pioneered the bringing together of multiple datasets to further our understanding of the significance of water for the environment within the Basin.

Note: The contents on this page includes summarised text from the following report: Basin-scale evaluation of 2022–23 Commonwealth environmental water: Ecosystem diversity. Page number references have been noted throughout the content below for anyone using the full report.

5 key areas of impact have been identified:

Each year, the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH) delivers water to ecosystems which are representative of the water-dependent ecosystems found throughout the Murray-Darling Basin and are vital for maintaining Basin biodiversity.

Our understanding of the ‘managed floodplain’ area within the Basin has deepened, as well as the CEWH’s ability to water it. For example, in 2022–23, the CEWH watered 53 of 64 (83%) of the ecosystem types found on the managed floodplain showing that CEWH watering is important for maintaining biodiversity.

Of the 16 Ramsar wetlands in the Basin, 12 are regularly supported by Commonwealth environmental water, often in collaboration with other environmental water holders. In 2022–23, approximately 1,050 gigalitres of water for the environment was delivered to Ramsar sites, comprising 437 gigalitres of Commonwealth environmental water. The CEWH delivered water to 8 Ramsar sites in 2022–23

CEWH water is critical in enabling Basin water-dependent ecosystems to be maintained in a variable climate. In alignment with Basin-wide environmental watering strategy (BEWS) annual priorities, the extent of watering by the CEWH varies with the climate, with more extensive use of water management to support floodplain and wetland ecosystems in wetter years to maximise ecological benefits, retracting to the focused protection of key aquatic ecosystems during droughts.

This theme has led to innovation in managing large quantities of data to understand patterns in space and time, which has seen the development of new ways to interpret and visualise large data sets in order to evaluate environmental watering of ecosystems at a landscape scale.

Helpful definitions

The Australian National Aquatic Ecosystem Classification (ANAE) is a systematic framework that categorises aquatic ecosystems in Australia, focusing on their ecological characteristics, functions, and values. It aids in biodiversity conservation, environmental water management, and policy development by providing a standardised approach to understanding aquatic habitats.

The managed floodplain is the estimated area of the Basin that can be influenced by environmental water management. It includes actively managed areas that can receive environmental water delivered from large headwater storages, or via ‘environmental works’ sites on the Murray River floodplain from The Living Murray Program. It also includes passively managed areas that receive environmental water via flow rules in water resource plans, or via natural events.

A ‘constraint’ as defined by the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, is anything that limits water from reaching floodplains, creeks, and wetlands. This includes physical barriers such as low-lying bridges and crossings, as well as operational factors such as river management rules or practices. These features of the river system developed over many years as industries and communities grew and rivers became more regulated. Constraints can reduce efficiency in the system, and hinder its ecological health, limiting the full environmental benefits of water recovered under the Basin Plan.

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, signed in 1971 in the town of Ramsar, Iran, is the first modern international treaty focused on conserving natural resources, specifically wetlands. It aims to halt global wetland loss and promote their sustainable management through international cooperation, policy-making, capacity building, and technology transfer. Australia has obligations under the Ramsar convention to care for wetlands listed under the Ramsar Convention.

Our approach

The Ecosystem Diversity evaluation explores the key question: How does Commonwealth environmental water contribute to the ecosystem diversity?

To do this, our work documents the range of water-dependent ecosystems that potentially benefit from environmental water, including at Ramsar sites, to evaluate the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water to the following Basin Plan objectives:

8.05(3)(b): to ensure that representative populations and communities of native biota are protected and, if necessary, restored; and

8.05(2)(a): to protect and restore a subset of all water-dependent ecosystems of the Murray–Darling Basin, including by ensuring that declared Ramsar wetlands that depend on Basin water resources maintain their ecological character.

This evaluation does not directly measure the responses of water-dependent ecosystems. Instead, it provides data that supports other related Flow-MER Themes of Vegetation, Fish, Food Webs and Water Quality, and Species Diversity, which offer more detailed reports on the responses of species, populations, and ecosystem functions within the Basin’s aquatic ecosystems.

The evaluation also supports the Flow-MER project’s focus on specific species groups such as fish, waterbirds, frogs, and plants, found across water-dependent ecosystems of the Basin.

This evaluation relies on 4 datasets:

The Australian National Aquatic Ecosystem (ANAE) Classification of the Murray–Darling Basin v3.0, which maps and classifies over 300,000 aquatic ecosystems into 66 ecosystem types (Figure 1).

The Ecosytem Diversity evaluation continues the sequence of annual and cumulative evaluation established during the Long Term Intervention Monitoring Project (LTIM from 2014–19). While the approach has not changed substantively from previous evaluations, the datasets and mapping have improved over time.

This has prompted a re-analysis of all previous hydrological inundation and ecosystem mapping data since monitoring began in 2014–15, so that we could incorporate these improvements and ensure results in the cumulative analysis are comparable among years.The approach and methods for this evaluation, including supporting references to technical analysis, are available from section 3 (page 6) of the evaluation report.

What we’ve learned

Does water for the environment benefit aquatic ecosystems?

Work in the Ecosystem Diversity theme has clearly shown the critical importance of Commonwealth environmental water to supporting and maintaining representative water-dependent ecosystems across the Basin. The extent, scale and impact of watering is described below in 5 key areas.

Watering a representative subset of aquatic ecosystem types

(pages iv-v; 14-15)

In the 2022-23 water year, the Commonwealth environmental water supported 53 of 66 ecosystem types (80% of the ecosystem types currently mapped in the Basin), and 83% of the ecosystem types found on the managed floodplain (53 of 64). In addition, the CEWH enabled end-of-system flows to support 23,768 ha of estuary habitat in the Coorong and Murray Mouth (100% of the estuary on the managed floodplain), and contributed to maintaining the ecological character of the Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Wetland Ramsar Site.

Over the 9 year period of 2014-23, the CEWH supported 56 ecosystem types (85% of the 66 ANAE ecosystem types in the Basin, and 88% of the 64 ANAE types currently mapped on the managed floodplain) representing:

- 38,813 ha of lakes representing 18% of lake area on the managed floodplain upstream of the Lower Lakes, or 123,336 ha (41% of lake area on the managed floodplain) for the Basin, including lakes Alexandrina and Albert

- 125,743 ha of 21 types of palustrine wetland (25% of the wetland area on the managed floodplain)

- 187,486 ha of 12 types of floodplain (12% of floodplain ecosystem area on the managed floodplain)

- 27,715 km of 7 types of waterway (52% of the river length on the managed floodplain)

- 23,768 ha of 9 estuarine ecosystems (100% of the estuary on the managed floodplain).

At the Basin scale, Commonwealth environmental water contributed to watering frequencies that were broadly consistent with expected requirements – with more frequent support of permanent rivers, lakes, meadows and permanent tall marsh, and less frequent inundation of temporary channels, swamps and floodplains.

Watering the ‘managed floodplain'

(pages iv and 14)

In 2022-23, Commonwealth environmental water supported 202,071 ha of lakes and wetlands of 21 different types, representing 64% of the lake and wetland diversity, and 14% of the total area of lakes and wetlands on the managed floodplain.

Commonwealth environmental water supported longitudinal connectivity through 22,205 km of rivers (41% of the river length on the managed floodplain). These were predominantly permanent and temporary lowland rivers (97% combined) that connected laterally with 71,837 ha of floodplain. This included 11 different floodplain vegetation communities, and represents 5% of the managed floodplain in the Basin.

Watering Ramsar sites

(pages v, 15, 24 and 26)

In 2022-23, the CEWH delivered 437GL of environmental water to 8 Ramsar sites in the Basin, supporting the following critical components processes and services (critical CPS):

- Maintenance of waterbird breeding rookeries that formed after widespread natural flooding at the Gwydir Wetlands: Gingham and Lower Gwydir (Big Leather) Watercourses; the Macquarie Marshes; Narran Lakes; and Barmah Forest Ramsar Sites.

- Vegetation listed as critical CPS at all sites, for example:

- 99 ha (100%) of freshwater meadows in the Barmah Forest Ramsar Site, with observations of growth and flowering of Moira grass

- nationally vulnerable river swamp wallaby-grass (Amphibromus fluitans) supported at Pollack Swamp in the NSW Central Murray Forests Ramsar Site)

- extensive inundation (2,676 ha, 99%) of the tall marsh of the Macquarie Marshes Ramsar Site

- extensive inundation (1,544 ha, 39%) of lignum in the Narran Lakes Ramsar Site.

Supporting the Basin Plan and BEWS by responding to annual needs and climate variability

Basin Plan (pages vi 66)

The Basin Plan sets high-level objectives to ensure that the water-dependent ecosystems of the Murray–Darling Basin are resilient to climate change and other risks and threats (Basin Plan section 8.04).

Objectives for the Protection and restoration of water-dependent ecosystems are set in Section 8.05, and for the Protection and restoration of ecosystem functions of water-dependent ecosystems are set out in Section 8.06. The following results outline the multi-year contributions of environmental water deliveries to realising these objectives.

Basin Plan objective at paragraph 8.05(3)(b): to ensure that representative populations and communities of native biota are protected and, if necessary, restored.

- Ecosystems that are in scope for environmental water management are broadly representative of ecosystem types elsewhere in the Basin. Of the Basin ecosystem types, 97% occur on the managed floodplain, and the relative abundance (by area) of ecosystem types is similar when comparing the managed floodplain to the whole Basin.

- In 2022–23, there were 53 ANAE ecosystem types, representing 83% of the ecosystem diversity on the managed floodplain, that received Commonwealth environmental water. They cover a combined area of 297,676 ha, with an additional 22,205 km of river representing the ‘populations and communities of water-dependent native biota’ that are assumed to have been supported or ‘protected’ by the environmental water they received. The evaluation is unable to examine if ecosystems were ‘restored’.

- The nine year watering history, 2014–23, included a similar diversity of ecosystem types, but a wide difference in the total extent. The past two years, 2021–22 and 2022–23, had the most extensive inundation by Commonwealth environmental water, with many actions to extend the duration of natural spring flooding into late summer to support completion of waterbird breeding and fledging of chicks. Ecosystems that are not watered are the naturally wet bogs, springs and paperbark swamps, and saline systems where delivery of fresh water is not needed.

Basin Plan objective at paragraph 8.05(2)(a): to protect and restore a subset of all water-dependent ecosystems of the Murray–Darling Basin, including by ensuring that declared Ramsar wetlands that depend on Basin water resources maintain their ecological character.

- Commonwealth environmental water was delivered to 8 Ramsar Sites in 2022–23, supporting a total of 164,935 ha of 51 different ecosystem types within the Ramsar estate. This areal extent is dominated by the 79,418 ha of lakes Alexandrina and Albert, and 18,845 ha of the Coorong. Excluding these three waterbodies in the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth (CLLMM), Commonwealth environmental water directly supported 66,672 ha of Ramsar ecosystems (see Ramsar sites section). Some evidence for supporting components, processes and services that define the ecological character of Ramsar Sites (critical CPS) were identified (e.g. protecting and/or maintaining frequency of inundation to support vegetation, which in turn supports breeding and foraging habitat for waterbirds). A detailed investigation to determine if Ramsar Site ecological character was maintained (the Basin Plan objective), was beyond the scope of this evaluation.

Basin-wide environmental watering strategy (BEWS) (pages iv, vi and 68)

Commonwealth environmental watering is responsive to climatic conditions from year to year, and sufficiently agile to deliver water in accordance with the Basin-wide environmental watering strategy’s annual priorities. For example, natural flooding in 2016–17 meant watering of floodplains was not a priority, but after two wet years in 2021–22 and 2022–23, the floodwater receded quickly in summer 2024, and there was extensive use of Commonwealth environmental water to support breeding waterbird rookeries. In the driest year on record (2019–20) Commonwealth environmental water was directed in-channel to support base flows and top-up refuge pools.

In the 2022-23 water year, vegetated ecosystems were supported in agreement with the Basin-wide environmental watering strategy’s annual watering priorities including:

- Non-woody vegetation priorities to provide opportunities for growth, saw Commonwealth environmental water delivered to 31,137 ha of meadow and marsh upstream of the Lower Lakes, 8,876 ha of marsh around the Lower Lakes, 5 ha of sedge/forb/grassland riparian zone or floodplain, and 22,205 km of river channel inundated.

- A rolling priority to maintain the extent, improve the condition and promote recruitment of forests and woodlands was met, with Commonwealth environmental water delivered to 69,888 ha of woody wetlands (swamps) and 71,303 ha of woody floodplain vegetation inundated.

- A rolling priority to maintain the extent and improve the condition of lignum shrublands, and an annual priority to support continued recovery of lignum shrublands at Narran Lakes and other key sites in the northern Basin were met, with 13,021 ha of lignum floodplain inundated, and another 298 ha of temporary lignum swamp receiving Commonwealth environmental water.

- An annual priority to support recovery of core wetland vegetation and emerging vegetation by supplementing natural flows at key sites in the Macquarie Marshes was met by watering a total of 25,561 ha of wetlands and 19,905 ha of floodplain in the Macquarie Valley including 10,232 ha (56%) of the Macquarie Marshes Ramsar site.

- A rolling priority to expand the extent and improve the condition of Moira grass in Barmah–Millewa Forest was met by Commonwealth environmental water combined with natural flooding that promoted Moira grass growth and flowering.

- Annual priorities to increase inundation higher on the floodplain to support parched and stressed forests and woodlands at key sites in the Lower Murray valley, and to provide flows to improve the health of black box communities higher on the floodplain, were met by extensive natural flooding. Commonwealth environmental water made a small contribution (less than 5% of the area of black box on the managed floodplain), with 93 ha of temporary black box swamp and 8 ha of black box woodland riparian zone or floodplain watered in the Central Murray Valley. There was little inundation of black box in the Lower Murray valley (1 ha representing <0.1%)

- A Basin-wide annual watering priority to support inundation of the Warrego floodplain was met, with 150 ha of floodplain and 1,240 ha of wetlands inundated by Commonwealth environmental water in the Warrego Valley.

Advancing data analysis, evaluation methods and application

The Ecosystem Diversity Theme has evolved over time to become a highly valued and important dataset to understand types of ecosystems Commonwealth environmental water supports across the Murray-Darling Basin. Key steps in this evolution of data analysis and application include:

- Development of the ANAE classification (2011-12): The ANAE was created to identify high-value aquatic ecosystems based on diversity, uniqueness, habitat, naturalness, and representativeness.

- Basin ecosystem map (2012): CEWH, VEWH, states, and MDBA mapped water-dependent ecosystems to standardise ecosystem classification and support environmental water management.

- Murray-Darling Basin Plan (2012): Launched with objectives to protect and restore water-dependent ecosystems, requiring a consistent classification method.

- Identifying the managed floodplain (2018): Introduced to guide environmental water management on specific floodplain areas, allowing overlay of ANAE classification to assess ecosystem diversity and representativeness.

- Capacity for ecosystem management: This dataset provides insight into which ecosystems can be managed with environmental water, helping to meet Basin Plan objectives.

- Annual water mapping: Enables yearly tracking of where environmental water goes and which ecosystems are reached.

- Evaluating ecosystem diversity: Developed ecosystem richness scale, identifying rich areas such as the northern basin and Coorong.

- Nine years of water patterns: Tracks water distribution at ecosystem and larger scales, with extensive data collection.

- Adaptive management implications: Improved understanding of watering patterns, especially for wetlands near channels and core rivers in dry years.

- Support for floodplain ecosystems: Data shows Commonwealth environmental water supports:

- 83% of water-dependent ecosystem types on the managed floodplain.

- 239,662 ha of lakes/wetlands, 157,907 ha of floodplain, 26,245 km of waterways, and 23,767 ha of estuary.

- Managed floodplain representativeness: The Ecosystem Diversity Theme has shown that Commonwealth environmental watering supports a diverse array of aquatic ecosystems on the managed floodplain that are representative of the diversity of aquatic ecosystems found throughout the Basin.

- Ecosystem condition assessment: Nine years of data enables ecosystem health assessment, showing trends in condition over time.

- Condition shifts in wet/dry periods: We can now use this living, breathing dataset to interrogate ecosystem condition shifts with climate and how environmental water plays a role in supporting these systems across these climatic shifts.

See the section entitled ‘Beating a path to ecosystem-scale evaluation’ that is a presentation Dr Shane Brooks gave on the above changes over time.

Informing adaptive management

(pages vii and 70)

Evaluation shows that Commonwealth environmental water is being used to manage ecosystems that are representative of the managed floodplain and, with the exception of high-energy upland streams, are a representative subset of water-dependent ecosystems in the Basin. Watering frequencies broadly align with expected needs of vegetation groups, with permanent lowland rivers, freshwater meadow and permanent tall marsh ecosystem types watered more frequently than most swamps, and palustrine wetlands watered more frequently than floodplains. Saltmarshes, salt lakes and bogs have not been watered.

The 9 years of inundation mapping have added another 10% by area to the managed floodplain, with the addition of 6,736 mapped ANAE wetlands and floodplains covering 359,091 ha. This improves our knowledge of the extent and number of ecosystems that are potentially in scope for environmental water management in the Basin.

Creation of a unified register describing the purpose, timing, duration and extent of all environmental water management, along with observed outcomes and any unintended consequences, would empower improved Flow-MER evaluation and inform the collaborative planning process.

Development of watering objectives for ecosystem types and expected ecosystem-scale outcomes would support a performance-driven evaluation to assess the impact of Commonwealth environmental water beyond the current simplistic view that documents the pattern of water delivery with assumed benefits.

Informing the planning and management of water to protect and restore ecosystem diversity in the Basin

The 9 years of continued evaluation of ecosystem diversity supported by Commonwealth environmental water is clarifying:

the spatial pattern of watering actions in the landscape among valleys at the Basin scale.

the distribution of Commonwealth environmental water to the different ecosystem types to ensure ecosystems receiving water are representative of Basin ecosystems.

watering frequencies at ecosystem and wetland-complex scales.

The 102 watering actions in 2022–23 inundated substantial areas (>1,000 ha total) of floodplains and floodplain wetlands in 9 of the 25 valleys of the Basin (page 15). Commonwealth environmental water delivered to the Broken, Campaspe, Goulburn, Loddon, Ovens and Wimmera rivers in Victoria was confined to the river channels, benefiting a small number of in-channel weir pools and connected wetlands. In the northern Basin, a similar pattern was seen with in-channel flows in the Namoi, Barwon Darling, and Border Rivers.

The largest areas of inundated wetlands and floodplain were from Commonwealth environmental water that was delivered to extend the duration of widespread natural flooding and provide cues to support aggregate waterbird breeding rookeries (Condamine Balonne, Lachlan, Gwydir, Macquarie and Murrumbidgee valleys), and fish movement and breeding (Central Murray, Murrumbidgee) (page 15).

Volume of Commonwealth water for the environment delivered to Murray-Darling Basin regions

Commonwealth water for the environment is used to support a range of ecosystems across the Basin, including Ramsar wetlands. The map below shows the number of ecosystem types on the managed floodplain in each valley supported by Commonwealth environmental water in 2022-23, including the Ramsar sites which received Commonwealth environmental water.

Commonwealth environmental water delivered to:

Watering actions:

Number of ecosystem types on the managed floodplain in each valley supported by Commonwealth environmental water

Commonwealth environmental water supported 83% of ecosystem types including 64% of the lake and wetland diversity and 14% of the total area of lakes and wetlands on the managed floodplain.

Commonwealth environmental water delivered 437 GL to 8 Ramsar Sites in the Basin supporting nominated critical components, processes and services.

13,021 ha of lignum floodplain inundated to support the continued recover of lignum shrublands at Narran Lakes and other key sites in the northern Basin.

What is the Australian National Aquatic Ecosystem Classification (ANAE)?

Ecosystem types in the Basin are defined by the ANAE Classification Framework. The framework was designed to support adaptive management and monitoring of water-dependent ecosystems across the multiple jurisdictions in the Basin, by providing a common language for describing and naming aquatic ecosystem types. The ANAE classification of the Basin v3.0 provides the most complete contemporary mapping of the distribution and extent of water-dependent ecosystems in the Basin. The areas of approximately 300,000 aquatic ecosystems have been mapped to 5 high-level system classes. These are further classified into 66 ANAE types, including: 8 types of lake, 29 types of palustrine wetland, 12 floodplain types, 8 river types, 9 estuarine ecosystem types, and waterholes and springs. They represent a combined area of approximately 83,000 km2 or nearly 8% of the Basin. Ecosystem diversity is quantified as the number of different ANAE types and their areas that received Commonwealth environmental water.

Only the larger rivers are mapped as areas. There are approximately 200,000 river features mapped, representing 50,000 km of perennial flowing rivers, and more than 400,000 km of temporary flowing rivers and streams. Because they are mapped as line segments, the ecosystems receiving Commonwealth environmental water are quantified by their river length (km), in contrast to the wetlands and floodplains that are quantified by area (hectares; ha).

Summary of ANAE types and contribution of Commonwealth envirinmental water on the managed floodplain

The table below (table 4.2 on page 21 in the report) shows lake and wetland ecosystem types on the managed floodplain which were supported* by Commonwealth environmental water in 2022–23; excludes the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth area, which is tabulated separately in the second table below, or table 4.5 (page 23) in the report.

*For this evaluation, river and floodplain ecosystem types are deemed supported by Commonwealth environmental water in the areas that are inundated. The inundated area is the floodplain area that is overlapped by the mapped extent of inundation.

The table below (table 4.5 on page 23 of the report) shows the Australian National Aquatic Ecosystem (ANAE) ecosystem types in the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth (CLLMM) supported* by Commonwealth environmental water in 2022–23.

*For this evaluation, river and floodplain ecosystem types are deemed supported by Commonwealth environmental water in the areas that are inundated. The inundated area is the floodplain area that is overlapped by the mapped extent of inundation.

Outcomes for Basin water-dependent ecosystems

Lake ecosystems

(pages 40-41)

Commonwealth environmental water was consistently delivered to 2 of the 8 lake types found in the Basin, but together they make up 92% of the lakes by area in the Basin and on the managed floodplain. Commonwealth environmental water was delivered more frequently for the maintenance of permanent lakes, except in 2020–21 and 2022–23, where water was delivered to the large temporary Lake Brewster (6,500 ha) in the Lachlan Valley to support pelican breeding and waterbird foraging. This pattern is consistent with the hydrological needs of these systems, as temporary lakes also require dry periods to maintain ecosystem processes.

The large increase in permanent lake inundation in 2017–18 (Figure below) was due to weir pool raising at Lock 8 and Lock 9 on the Murray River to push Commonwealth environmental water into Lake Victoria (a 10,738 ha permanent lake), to temporarily hold some water in a wet year for delivery at a later time (page 41).

Wetland ecosystems (palustrine)

(pages 42-44)

Definition:

Palustrine wetlands are shallow wetlands with a predominance of emergent vegetation (reeds, sedges, shrubs or trees).

There are 29 ANAE palustrine wetland types in the Basin, with 15 of the most common representing 99% of the total Basin wetland area. The managed floodplain contains 39% of Basin wetland area, comprised of the same 15 common types in similar proportions to the whole of the Basin. The palustrine wetlands on the managed floodplain, in scope for Commonwealth environmental water, are therefore qualitatively representative of palustrine wetlands in the Basin.

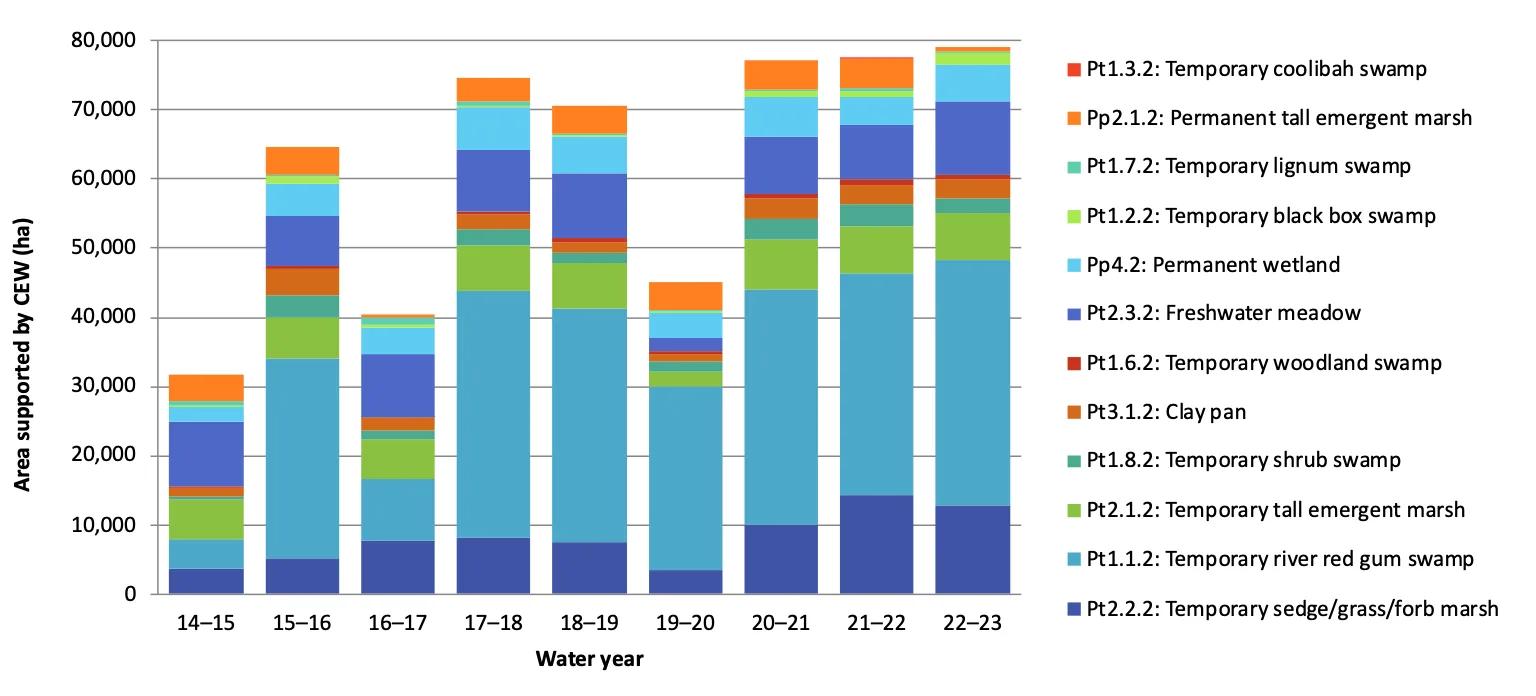

In the 9 years 2014–23, Commonwealth environmental water supported 125,743 ha of palustrine wetland of 21 different ANAE wetland types figure below.

Between 32,666 ha (2014–15) and 79,955 ha (2022–23) were watered in any one year (average 63,585 ha), with 15 wetland types (4,181 ha combined) receiving Commonwealth environmental water in every year. 8 wetland types did not receive any Commonwealth environmental water (values exclude the CLLMM). Including the CLLMM adds another 19,000 ha supported by Commonwealth environmental water (mostly fringing marshes and unvegetated depressions around lakes.

Temporary river red gum swamp was the wetland type with the largest area supported by Commonwealth environmental water over the 9 years (37,781 ha). Most of this area was inundated in seven of the nine years since 2014–15, corresponding to the years the Barmah–Millewa Forest received an allocation from the Commonwealth. Temporary river red gum swamp is an ecosystem type that is commonly supported by environmental water, due to its proximity and connectedness to lowland river channels. Fringing river red gums and swamps that are connected to waterways often receive water during channel freshes or weir pool raising actions, in addition to actions that specifically target overbank flooding. For example, weir pool raising at Locks 7–9 on the Murray River floods river red gum swamps and anabranches around Lindsay, Wallpolla and Mulcra islands.

Ecosystem types that did not receive Commonwealth water at all over nine years included 14,241 ha of saline systems (salt flats, saline wetlands and salt marsh) for which freshwater additions could be detrimental, and 187 ha of ecosystems that are consistently wet, and perhaps not in need of supplementary water (permanent springs, paperbark swamps, peat bogs and fen marshes).

The proportion of palustrine wetland types supported by Commonwealth environmental water was similar across all 9 years, with 3 notable exceptions:

- There was reduced watering of temporary river redgum swamp in 2014–15 and 2016–17, when Commonwealth environmental water was not used to inundate the river red gum dominated Barmah–Millewa Forest (The Living Murray Program delivered environmental water to Barmah–Millewa in these 2 years).

- Watering of temporary tall emergent marsh and freshwater meadow was lowest in 2019–20, when there were no significant overbank flows in the Gwydir Wetlands and Macquarie Marshes.

- There was no watering of permanent tall emergent marsh in 2016–17 due to widespread natural flooding. Note that 2022–23 was also a year with widespread natural flooding; however, in this year, tall marshes in the Macquarie Marshes and Gwydir Wetlands received Commonwealth environmental water to extend the flood duration, to support waterbird breeding.

Floodplain ecosystems

(pages 44-46)

Approximately 28% of floodplains in the Basin align with the managed floodplain, and all 12 Basin floodplain ANAE types are represented there. The most common floodplain ecosystem types in the Basin (coolibah woodland and black box woodland floodplains) occur higher on the floodplain away from rivers, with only 24% of coolibah woodland floodplain and 17% of black box woodland floodplain located on the managed floodplain. In contrast, river red gum has a higher water requirement and is found lower on the valley floors closer to rivers, leading to a higher proportion of Basin river red gum (49%) being located on the managed floodplain. Despite these differences, the floodplain types located on the managed floodplain are representative of Basin floodplains.

Limited water volumes and policies to avoid inundating built assets or agricultural land often constrain Commonwealth environmental water to in-channel flows and watering of floodplain wetlands through regulators, and connecting channels rather than by overbank flooding. On average, from 2014–15 to 2020–21, only 3% of the managed floodplain received Commonwealth environmental water in any one year (area of all ANAE floodplain types). In 2021–2022 and 2022–23, Commonwealth environmental water was delivered to the Macquarie Marshes, Gwydir Wetlands, Narran Lakes and Lowbidgee to support the maintenance of water at waterbird breeding rookeries that formed in response to extensive natural flooding. As a result, the extent of floodplain supported by Commonwealth environmental actions in the most recent 2 years (2021–23) was higher than in any previous year (average 72,947 ha, 5% of the managed floodplain) (Figure below). Over the 9-year period of monitoring, 187,416 ha of floodplains (187,486 ha including the CLLMM), comprising 12% of the managed floodplain, was inundated by Commonwealth environmental water at least once.

River red gum forest riparian zone/floodplain was inundated by Commonwealth environmental water to the greatest extent, with 71,356 ha inundated over the 9 years at varying frequencies, representing 22% of this ecosystem type on the managed floodplain (Figure below). River red gum forest and woodland floodplain types comprised between 32% and 82% of the floodplain area inundated in any one year over the last 9 years. This reflects the proximity of river red gum ecosystems to river channels, and the high value of river red gum in priority assets (e.g. Barmah–Millewa Forest, the Lowbidgee floodplain and Macquarie Marshes).

The pattern of watering across years, seen in the Figure below, reveals some contrasts. The 2 years with the least floodplain inundation were 2016–17 and 2019–20: 2016–17 was a very wet year where watering of floodplains by Commonwealth environmental water was not seen as a priority; 2019–20 was the driest year on record and available Commonwealth environmental water was directed to supporting base flows, with only 2 of 155 planned watering actions targeting overbank flows. The 2021–23 period was also very wet, but unlike 2016–17, there was extensive use of Commonwealth environmental water to support completion of waterbird breeding in late summer, after winter rains reduced.

River ecosystems

(pages 46-48)

The managed floodplain contains 11% of the total river length in the Basin. This includes 76% of the total length of permanent lowland rivers in the Basin, and 24% of the temporary lowland river length. On the managed floodplain, lowland rivers dominate representing 86% of the 53,542 km total river length that is estimated to be in scope for water management (47% temporary lowland rivers and 39% permanent lowland rivers). With such a high proportion of these river types present on the managed floodplain, it is likely these ecosystems are representative of the other lowland rivers in the Basins. The 6 transitional and upland stream ecosystem types on the managed floodplain (7,485 km, 14%) are generally high-energy outflow channels from storages, before they flow out into the flat lowlands of the central and western Basin.

Commonwealth environmental water primarily supports permanent and temporary lowland rivers, with 97% of flow delivery in any one year being in lowland reaches. At the Basin scale in 2014–23, the annual allocation to river flows was very consistent, with 14,102 km up to 22,211 km of waterways potentially benefiting from Commonwealth environmental water annually (Figure below).

Over the 9-year period, 27,715 km of river was supported by Commonwealth environmental water (52% of all the river length on the managed floodplain), with 35% (9,609 km) watered in every year along permanent lowland sections of the Barwon, Macquarie, Gwydir, Lachlan, Murrumbidgee, Edward/Kolety–Wakool, Murray, Ovens, Broken, Goulburn and Loddon rivers. Permanent reaches in the lowland sections of the Bokhara, Culgoa, Darling and Campaspe rivers, and the smaller upland, transitional Severn River, received Commonwealth environmental water in 8 of the 9 years. Some temporary rivers have also received water in 7–8 of the years: Gunbower Creek, Tuppal Creek, the Moonie River, and the lower end of the Warrego River.

The upland and transitional streams that received Commonwealth environmental water were mostly outflows from storages into the upper reaches of the King, Lachlan, Gwydir, Severn and Dumaresq rivers. However, there were some unregulated flows managed by water licence rules – in the Severn River above Glenlyon Dam (7 in 9 years) and in the upper Warrego River (5 in 9 years).

Extent of managed floodplain

The managed floodplain was initially mapped by MDBA in 2018. Approximately 32% of the Basin’s total area of lakes occurs on, or adjacent to, the managed floodplain, as well as 37% of total Basin palustrine wetland area, 25% of floodplains and 10% of river lengths (page 11).

The Long Term Intervention Monitoring Project and the Flow-MER program have mapped inundation by Commonwealth water annually since 2014 using satellite imagery and observations by water managers. These maps provide 9 years of additional evidence to support an update to the managed floodplain extent, as, by definition, all areas watered using Commonwealth environmental water are ‘managed’.

The 9 years of monitoring has enabled us to add 359,091 ha to the managed floodplain, a 10% increase over the 2014 mapping. This additional area intersects 6,736 mapped ANAE wetlands and floodplains, increasing our knowledge of ecosystems ‘in scope’ for environmental water management. All figures and tables used in the Ecosystem Diversity report for 2022-23 and on this page that refer to the managed floodplain are using the revised 2024 managed floodplain extent.

Outcomes for Ramsar Sites

There are 16 Ramsar wetlands in the Basin, of which 12 are regularly supported by allocations of water from the Commonwealth, the Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) (e.g. The Living Murray Program), and state jurisdictions.

Commonwealth environmental water was allocated to 11 sites over the period of monitoring 2014–23. The Kerang Wetlands Ramsar Site is managed solely by Victoria, and 4 Ramsar Sites in the Basin currently cannot receive managed environmental water: Currawinya Lakes and the Paroo River Wetlands are in unregulated northern Basin locations, and Ginini Flats Wetland Complex is in the alpine region above any water storages.

The fourth site, Lake Albacutya, is the second of 2 large terminal lakes at the end of the Wimmera River – there is currently an insufficient volume of water in the system to first fill Lake Hindmarsh so that water can spill to Lake Albacutya.

In 2022–23, approximately 1,050 GL of environmental water, containing 437 GL of Commonwealth environmental water, was delivered to 8 Ramsar Sites in the Basin. In many instances, environmental water delivered to floodplains is returned to the river and used again to inundate sites downstream. For example, water in the Barmah Forest Ramsar Site flows back into the Murray, and then can be used to inundate Gunbower Forest, Hattah–Kulkyne Lakes and Riverland Ramsar Sites further downstream. Environmental water that reaches the Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Wetland Ramsar Site mainly comprises return flows from upstream watering.

The evaluation of ecosystem diversity supported by Commonwealth environmental water in Ramsar Sites differs from the Basin-scale method, using the ANAE polygon mapping for riverine ecosystems instead of the Basin-scale river line mapping. The ANAE polygon mapping is not used at the Basin scale because it does not include all rivers in the Basin. It is, however, complete within the limited extent of the Ramsar estate, allowing all ecosystem types within the Ramsar Sites to be compared by the mapped area, and the area that received Commonwealth environmental water.

The Ramsar site river polygons are assessed using the same logic applied to lakes, where the entire area of river polygons within Ramsar Sites are deemed supported by Commonwealth environmental water when overlapped in whole or in part by the satellite-derived inundation extent. At most Ramsar Sites, the water is delivered to the site via the river channel and occupies the whole channel.

Banrock Station Wetland Complex

(pages 54-55)

At the time of listing in 2002, Banrock Lagoon was managed as a permanent wetland, but it is now managed for a wetting and drying cycle each year – wetting during spring, primarily to sustain dominant vegetation associations, with a drawdown over summer and autumn. Commonwealth environmental water was delivered to support the hydrological character of the Banrock Station Wetland Complex Ramsar Site in 7 of the 9 years 2014–23 to maintain this cycle. In 2022–23 the water needs of the site were met by natural flooding. The frequently inundated patches on the eastern bank of the Murray River are patches of lignum floodplain outside the Ramsar Site boundary. Areas of permanent wetland are watered in the central basin to support threatened southern bell frog (Litoria raniformis). A regulator installed in Wiggley Reach in 2020 allows Commonwealth environmental water to be delivered to black box floodplain that supports the threatened regent parrot (Polytelis anthopeplus).

Barmah Forest

(pages 55-57)

Barmah Forest Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in 7 of the 9 years 2014–23. During the 2 years that Commonwealth environmental water was not delivered, there were 2 natural floods in 2014–15, and ‘other’ environmental water (state and MDBA’s Living Murray Program) was used to inundate the site in 2016–17. The annual flooding is thought to mimic the natural regime for the site, as high winter–spring flows are constricted by the narrow channel of the Barmah choke, causing river water to back up and divert through channels in the floodplain. It is estimated that under pre-regulation scenarios, the site would have naturally flooded in 19 of the past 20 years. The extensive inundation in 2021–22 is the result of a large environmental water allocation of 414 GL (including 220 GL of Commonwealth environmental water) that was delivered to the site when it was already 45% inundated by naturally occurring high flows.

The Ecological character description (ECD) for the Barmah Forest Ramsar Site notes that, at the time of listing, the hydrological regime may have been insufficient to maintain the character of the site in the long term, emphasising that regular managed inundation by environmental water in dry periods is critical to maintaining and restoring the site.

Fivebough and Tuckerbil Swamps

(pages 57-58)

Fivebough and Tuckerbil Swamps Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in 4 of the 9 years 2014–23. Fivebough Swamp is a permanent shallow wetland that was ‘topped up’ after 2 dry years in 2018–19 and 2020–21 using Commonwealth environmental water, to support its value as a significant waterbird drought refuge and waterbird feeding and breeding site. Tuckerbil Swamp is a brackish, seasonal shallow wetland maintained by Commonwealth environmental water more frequently (4 of the last 9 years) to support migratory waterbirds and threatened waterbird species, including brolga (Grus rubicunda), Australasian bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus) and Australian painted snipe (Rostratula australis). The swamps were inundated by natural flooding in 2022–23.

Gunbower Forest

(pages 58-59)

Commonwealth environmental water has been used in Gunbower Creek annually since 2015–16 to maintain native fish habitat and breeding. Gunbower Creek flows into the northern end of the Ramsar Site and regulators permit watering of adjacent wetlands. The Ramsar critical CPS include the ongoing presence of Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii) and silver perch (Bidyanus bidyanus) in Gunbower Creek, and small-bodied fish in wetlands within the Ramsar Site, including Australian smelt (Retropinna semoni), carp gudgeons (Hypseleotris spp.), dwarf flat-headed gudgeon (Philypnodon macrostomus), flat-headed gudgeon (Philypnodon grandiceps), fly-specked hardyhead (Craterocephalus stercusmuscarum), and Murray-Darling rainbowfish (Melanotaenia fluviatilis). The Ramsar critical CPS for Gunbower Forest also include waterbird breeding and maintaining the extent and condition of river red gum floodplain, but these have not been objectives for Commonwealth environmental water during the monitoring period 2014–23.Wetland inundation by environmental water has not been mapped at this site, but occurred in 2021–22 within some smaller wetlands connected to Gunbower Creek in the northern end of the site.

Gwydir Wetlands: Gingham and Lower Gwydir (Big Leather) Watercourses

(pages 51-52)

The Gwydir Wetlands: Gingham and Lower Gwydir (Big Leather) Watercourses Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in 8 of the 9 years 2014–23. The exception in 2019–20 was when flows were constrained to the channel to protect river assets after 3 successive years of dry conditions. In early 2020, there was above average rainfall that provided a natural water source to revive the cooch grass meadows, and high flows have been maintained keeping the wetlands inundated from May 2021 – March 2023. In these wet years, Commonwealth environmental water was used to extend the duration of inundation over summer to keep water in waterbird nesting and foraging habitats until summer breeding was completed. The Ramsar Site consists of 4 isolated sub-units with Commonwealth environmental water primarily supporting Goddard’s Lease and Old Dromana, to support freshwater meadows dominated by water cooch and areas of tall marsh. The Gwydir River System Selected Area reports in detail on the outcomes from Commonwealth environmental water management at this site. This site does not have an ECD that defines the critical CPS.

Hattah-Kulkyne Lakes

(pages 59-60)

In recent history, Hattah Lakes would connect to the Murray River via Chalka Creek when flows in the Murray River at Euston exceeded 36,700 ML/day. The ecological character of the site is now highly dependent on managed environmental water. Construction of a permanent pump station, regulators and environmental levees were completed as part of The Living Murray Program in 2014–15, when LTIM monitoring began. The pump infrastructure was used to deliver Commonwealth environmental water in 4 of the 9 years 2014–23. Watering ceased in 2019–20, to begin a planned ‘dry phase’. Recent reporting from The Living Murray Program indicates the lakes were dry in 2022–23. In the intervening years of 2016–17 and 2018–19, the floodplain was watered with contributions from The Living Murray. Mapping of other sources of environmental water in LTIM was not considered reliable or sufficiently comprehensive, and was discontinued in Flow-MER. Expanding the scope of this evaluation to include all water is recommended to provide a more accurate characterisation of the hydrological regime and, therefore, the contribution of Commonwealth environmental water as part of that regime. The lakes were partially filled in 2021 by Victorian environmental water aligned to high natural flows in the Murray River, and they drained back to the Murray over the summer. During winter and spring 2022, Victorian environmental water was delivered to the lakes, which were then flooded naturally by a flood event that was the largest since 1956 and estimated to have inundated 16,842 ha, compared to the 6,000 ha that can be inundated with environmental water alone.

Macquarie Marshes

(pages 53-54)

Commonwealth environmental water contributed (along with jurisdictional water) to inundation of the Macquarie Marshes Ramsar Site, in 8 of the 9 years 2014–23. No inundation is shown for 2019–20. However, in this period approximately 4 GL of Commonwealth environmental water was accessed through supplementary licences on the Macquarie River, allowing some in-channel flows to replenish refuge pools and flow through to the marshes. Extensive inundation in 2022–23 was the result of watering actions following natural flooding events, to maintain waterbird breeding rookeries and provide waterbird foraging habitat.

Water management in the Macquarie Marshes is typically planned and executed for the larger extent of the marshes, and not just the 3 units that make up the Ramsar Site. Much of the southern marsh that is regularly inundated by Commonwealth environmental water is outside of the Ramsar Site boundary.

The Ramsar critical CPS for the site include indicators that are the focus of much of the jurisdictional monitoring, including the extent of tall marsh, lignum and river red gum, waterbird counts, and aggregate waterbird breeding.

Narran Lakes Nature Reserve (Narran Lakes)

(pages 52-53)

The Narran Lake Nature Reserve Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in 5 of the 9 years 2014–23. Substantial inundation of lignum floodplain in 2019–20 has been followed up with water allocations in 2020–23 to improve lignum health and build resilience in the system, to support waterbird breeding and recruitment. Significant natural flows in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 years have maintained inundation at the site. Supporting regular breeding of aggregate-nesting waterbirds (in no less than 1 in 9 years) is listed as a critical service that characterises this site. Waterbird breeding commenced at the site after natural flooding in 2021–22, and again in 2022–23.Commonwealth environmental water was used to maintain water at rookeries through to the end of summer to provide breeding habitat and foraging areas for juveniles.

NSW Central Murray Forests (Koondrook and Werai forests)

(pages 61-62)

The NSW Central Murray Forests Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in 7 of the 9 years 2014–23. The site consists of 3 large river red gum forest groups: Millewa, Koondrook–Perricoota and Werai. The majority of environmental water is delivered via the Murray River, typically inundating approximately 4,000 ha or more of the Millewa section in conjunction with the Barmah Forest Ramsar Site on the opposite bank of the Murray River. In 2022–23, 214 GL (including 145 GL of Commonwealth environmental water) was delivered via the Murray when the site was already inundated by naturally occurring high flows resulting in 5,189 ha or 17% of the Millewa block being inundated. In 2016–17, the Barmah and Millewa sites were watered with 155 GL from The Living Murray Program to provide the annual inundation cycle for both the Barmah and Millewa forests combined.

Wholesale inundation of the Millewa group is likely to contribute to the maintenance of the ecological character of the site. The ECD for the site defines ecological character at large spatial scales, based on the current measured extent of marshes and river red gum forest in each of the forest blocks. For example, there should always be more than 20,000 ha of river red gum forest in the Millewa group, and loss of forest extent would represent a change in character. Hydrological requirements defining the character of the site are defined using recurrence intervals of floods in the Murray River. For example, maintaining channels and low-lying areas in the Millewa group requires a minimum of 5 high flows of more than 12,500 ML/day for 70-day durations downstream of Yarrawonga in any 10-year period.

Outside of the Barmah–Millewa, Commonwealth environmental water was only used at Pollock Swamp in the Koondrook group, a 700 ha nature reserve at the western end of the Ramsar Site (approximately 1% of the Ramsar Site area). A new program commenced annual pumping from the Murray in 2018–19, with 2–3.5 GL of Commonwealth environmental water released to restore approximately 100 ha of shallow wallaby grass and river red gum swamp. This project is likely to have successful outcomes, but, at this local scale, is a small contribution towards maintaining the ecological character of the Ramsar Site where critical CPS are defined at much larger scales. The remainder of the extensive Koondrook Forest Group (34,524 ha) and the Werai Forest Group (11,421 ha) have not received Commonwealth environmental water since monitoring began in 2014.

Riverland

(pages 62-63)

The Riverland Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in all 9 years 2014–23, inundating the site to varying degrees. The site is a large floodplain of the Murray River that includes the Chowilla and Calperum wetlands, and has many interconnecting channels and anabranches. Water is managed strategically through regulators and pumping to protect waterbird habitat and water-dependent vegetation, including stands of black box higher on the floodplain. The ECD defines hydrological character by the water requirements of different wetland types, which align to the Basin ANAE mapping, to use in evaluating the contribution of environmental water to maintenance of the Ramsar Site ecological character. For example, the bar chart below shows that Commonwealth environmental water is supporting a high diversity of ecosystem types at the site and appears to be used to protect the more permanent habitats, with larger areas of inundation of permanent wetland, permanent lake, permanent saline wetland and the permanent lowland river (the Murray River).

The Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Wetland

(pages 64-65)

The Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Wetland Ramsar Site received Commonwealth environmental water in all 9 years, either as allocations or end-of-system flows. Some attempts were made during LTIM to model changes in the large lake area in response to the relatively small quantities of environmental water received. However, the models were not sensitive enough to detect changes in inundation of wetland habitat that fringes the lakes. Flow-MER therefore uses the same inundated extent to represent the CLLMM in every year, and the composition of CLLMM ecosystem types supported by Commonwealth environmental water is mostly static, except for some small fringing areas that receive targeted allocations of water. For example, there was environmental watering of the Tolderol Game Reserve 2019–20 and 2020–21, and the Milang Snipe Sanctuary 2016–17 to 2021–22, to support migratory waders.

.avif)