With the extensive flooding and rainfall that has occurred throughout much of the Murray-Darling Basin, Nature has delivered its own “environmental water” to the catchment this year.

Some of the unregulated flood water has flowed into ephemeral creeks in the Edward/Kolety–Wakool River system, either by overbank flows or by opening of regulators. The creeks have been targeted for ecological monitoring in a new research project that is part of the Edward/Kolety–Wakool Flow-MER program, funded by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH).

“CEWH is funding the ephemeral creeks project to obtain additional knowledge to help deliver environmental water into the future, and/or to make decisions about further monitoring,” says Professor Robyn Watts from Charles Sturt University (CSU) and Program Leader.

Historically, before river regulation and agricultural modifications to the landscape, these ephemeral creeks would have flowed during large flow events. Then, as the water in the creeks dried up, they would revert to become a series of waterholes/refuge pools, some small, some large, up to kilometres long.

However, many of these ephemeral creeks are now disconnected for extended periods of time from the rivers and permanent creeks that would have once supplied them with water and, without environmental water, would be dry most years.

“Reduced flood frequency due to river regulation has meant that the ephemeral creeks in the system have had a lot less water than they would have had naturally,” says James Dyer, Environmental Water Management Officer with NSW Department of Environment and Planning (DEP), one of the partners in the ephemeral creeks project.

“So, we’ve been using irrigation infrastructure [owned by Murray Irrigation Limited] to deliver water to the creeks more frequently. Without environmental water these creeks would be dry nearly all the time except in big flood years such as this one in 2022.”

Addressing the knowledge gap

Ephemeral creeks are an important part of the landscape and the river ecosystem.

“The refuge pools provide habitat for many native species including threatened species such as Southern Bell frogs,” says Professor Robyn Watts. “Over the past few years CEWH has delivered water into these ephemeral creeks, and we need to know more about them.”

The ephemeral creeks project is addressing that knowledge gap. The project has three components:

1. Survey of the fish population before and after the flood using fyke nets and backpack electrofishing, led by Senior Technical Officer John Trethewie (CSU), assisted by staff from NSW DPE and Indigenous Rangers from Yarkuwa Indigenous Knowledge Centre, Deniliquin.

2. Survey of vertebrates in the refuge waterholes using eDNA [environmental DNA] analysis, led by Dr Meaghan Duncan, NSW Department of Primary Industry (DPI). The eDNA component of the project involves the researchers taking filtered water samples then, using a metabarcoding DNA analysis, to see what was in the water from the vertebrate cells present. “Meaghan will be testing for the presence of fish as well as other vertebrates, such as water rats (rakali),” says Robyn. “We are doing this additional eDNA sampling because the traditional fish surveys might not pick up some of the taxa.”

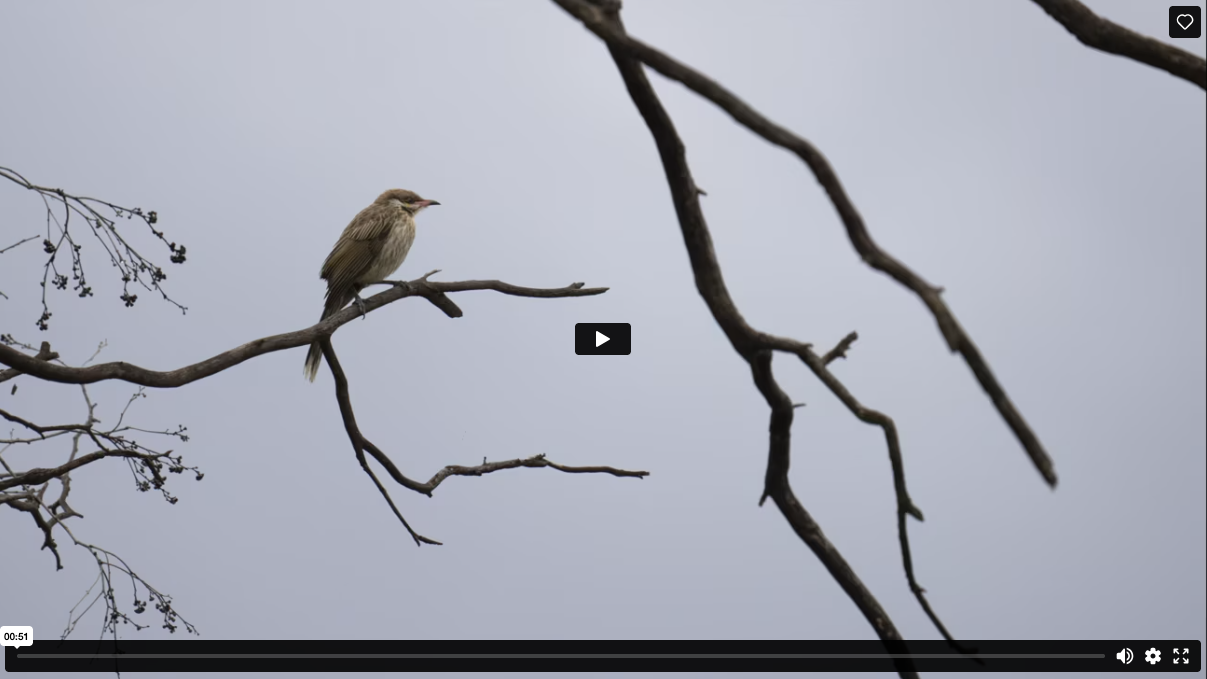

3. Surveys of birds and frogs before and after the flood, led by Dr James Dyer (birds) and Dr Helen Waudby, (frogs) DEP.

The researchers were able to do their first round of sampling and get their first surveys completed in August 2022 at the six project sites – Tuppal Creek, Thule Creek, Cockrans Creek, Jimaringle Creek, Yarrein Creek and Murrain Yarrein Creek – prior to the floodwater arriving.

“This will tell us what species have remained in these refuge waterholes since the previous environmental watering action in spring/summer 2022,” says Robyn.

The flooding in October/November 2022 together with heavy rainfalls meant it was difficult to access many of the sites as planned for the second round of monitoring. “I had planned to monitor when the environmental water came through, but instead of them ‘turning the tap on’, the water just came from everywhere,” says John. “It will mean tweaking the design of the project a bit. Once the flows settle down to a reasonable level, I’ll go back in and do some sampling then.”

In May/June 2023, by which time the creeks are expected to be a series of pools, the researchers will return to do the post-flood monitoring. The final report on the project will be completed by the end of 2023.

“The project is about increasing connectivity and maintaining key refuges, which links back to one of the objectives of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan,” says Robyn. “We want to find out what fish from the permanent river systems move into these temporary systems, what fish stay in them over winter, and if they survive are they breeding in these systems.”

The ephemeral creeks project is indicative of a broadening research focus in the Flow-MER Program.

“The monitoring of environmental watering actions initially focussed on the tributaries in the Edward/Kolety–Wakool system,” says Robyn. “The current Flow-MER Program has expanded and now includes the permanent rivers and creeks (e.g., Edward/Kolety, Yallakool ,Colligen- Niemur, and Wakool River) ); forests – (e.g. Werai Forest); and now the ephemeral creeks that we are monitoring.”

Robyn says this change in focus from a “site to system perspective” was in line with the greater emphasis by water managers on ensuring increased connectivity in river systems.

“In addition to monitoring environmental watering actions we are interested to learn more about responses during unregulated flooding, and all of this information can help inform water management,” says Robyn.

Hear what landholder Dennis Gleeson has to say…

Anthony Wilson (CEWH local engagement officer) and landholder Dennis Gleeson (right) with Cockrans Creek in the background. Pic J. Dyer

Dennis, whose main property is ‘Colligen Creek Station’, is a member of the Edward Kolety-Wakool Environmental Water Reference Group which was formed in early 2016 to ensure a local voice in the use of environmental flows in the Edward Kolety-Wakool River system. The Edward/Kolety–Wakool Flow-MER team provide regular updates on the outcomes of the monitoring and research at each of the Reference Group meetings.

Dennis owns several properties where the Edward/Kolety–Wakool research team have been doing monitoring since 2011, including one at the top end of Cockrans Creek, one of the ephemeral creeks being monitored, and another with Gwynes Creek running through it.

He says the last time he saw the creeks flowing like they are presently [beginning of November 2022] was in 2016.

“But even then, some of the creeks didn’t get water because of the levee banks etc.” says Dennis. “But this year most of them have filled up with unregulated water because we’ve had a lot of rain as well. It’s marvellous what you can do just by redirecting a little water. We’ve got water going into the top end of the Cockrans before it runs into Jimaringle Creek. There’s been no water in there since 1975 but now it’s running really well, not flooding water, and the landholders down there are really rapt.”

Unfortunately, this year, a lot of Dennis’s paddocks have flooded and he has lost thousands of acres of crops “but that’s been because of the rain, not because the water has come over the banks of the creeks.”

Dennis is very supportive of environmental water being delivered to the ephemeral creeks through the Murray Irrigation Limited (MIL) escapes and of the research being done to better inform those deliveries.

“We don’t need a flood to get water into these creeks through the regulators,” he says. “The environmental water is great for the bird life, and it’s great for the trees that were dying, that hadn’t had a drink for some time, and it keeps the fish in the refuge pools alive…we’ve got Murray Cod, some up to a metre long, in those pools…it keeps the creeks alive.

“It doesn’t need to be a whole lot of water; our creek system is one that would have only run every four to five years naturally in the past but with the changes to the whole area with irrigation channels going through, roads and things like that, these creeks are now disconnected from the main tributaries and creeks.

“The information that the scientists are getting will help with the decisions to put water into these systems.”

Hear what landholder Les Gordon has to say…

Les Gordon’s property, ‘Inglebrae’, at Burraboi, is further down the creek from Denis’s with the ephemeral Jimaringle Creek running through it. He has an area of “native vegetation that is water dependent” on his property that he’s been preserving that got its first environmental water in 2003 and is now “in really good condition.”

“It’s not a big area but its rich ecologically,” says Les. “And we’ve ended up with a well-established wet area in Jimaringle Creek. Our part of the creek gets natural water reasonably regularly but what tends to happen is that it doesn’t come from the top, it backs up from the Niemur River, if the Niemur has good flow. But while that happened initially this year, now it is flowing the right way, downstream and at a rate of knots.”

Les says he likes seeing water in the ephemeral creeks.

“In a lot of ways, it comes back to personal values,” he says. “I like having the creek in a good ecological condition. Big lengths of the creek have had exclusion fencing for a long period of time so there is good understory with all sorts of birds and even echidnas. There is a real visual amenity …I value it, I like having it there, it looks attractive, it is natural….but if these ephemeral creeks were full of water all the time they would fill up with grasses, sedges, black box suckers and cumbungi which is what has happened in the refuge areas.

“On the other hand, if you get a flood like the one we are now experiencing, that all drowns out and the cycle starts all over again. So where is that balance between having the creeks full of water regularly enough to sustain the system, but not overwatering it which is what happened through the 70s and the 80s? I don’t know where that line is.

“And this is where the monitoring becomes important and why I like having it happen on my land. Without monitoring and without saying what are we trying to achieve, there’s a whole lot of other variables we haven’t even begun to consider other than that water equals life.

“Monitoring helps provide answers.”

He gave the example of something he learnt from researcher John Trethewie who found baby turtles while monitoring the creek.

“The first thing John asked me was about my fox control, which we actively do mostly to protect little mammals and birds, but I didn’t realise that the foxes predate the eggs in the turtle nests,” says Les. “That has renewed our enthusiasm for fox baiting significantly. And I learnt something out of that process… we were getting a benefit we never knew about or had factored into our efforts but what was important in the process was that exchange between scientist and us as the landholders. That’s where I find participating in these research projects really valuable.”

Les, who works with other scientists including Dr Helen Waudby and Dr Matt Herring (Bitterns in Rice) says having access to scientists to ask questions is valuable.

“I never wonder anymore,” he says. “If I see something I’m wondering about I record it somehow and I send it to the relevant scientists and ask what’s going on here…and that’s really valuable because it is empowering us, as landholders, to do stuff.”

%20flowers-%20(photo%20credit-%20Rebekah%20Grieger).jpg)

%20.jpg)