Higher diversity of turtle species observed at wetland sites which receive environmental water delivery

By Anna Turner | Murrumbidgee Monitoring Evaluation and Research (MER) Program

The Murrumbidgee River, including its tributaries and wetlands, is home to three species of freshwater river turtles. Two of these species fit in the genus Chelodina, known as snake-neck turtles. Most commonly encountered is the Eastern long-necked turtle (Chelodina longicollis), easily identified by its long neck, and black and white patterning on the underside of its shell. Eastern long-necked turtles breed in early summer and the female will lay between 2 and 10 eggs in the bank near her aquatic habitat. It takes 3 to 5 months for the hatchlings to break out of their shells and a single female can lay one to three clutches of eggs per year. Eastern long-necked turtles are carnivorous and eat a varied diet including insects, worms, tadpoles, frogs, small fish, crustaceans, molluscs, plankton and carrion (dead animals).

Figure 1 Left: Hatchling Eastern long-necked turtle detected during FlowMER wetland monitoring. Photo credit: Sarah Talbot. Right: Adult Eastern long-necked turtle detected at Banim Swamp in the Gayini Nimmie-Caira wetlands, Lower Murrumbidgee. Photo credit: Anna Turner

The Broad-shelled turtle (Chelodina expansa) is the largest of the three turtle species, it also has a long neck however the head is broader and the shell lacks the black patterning in the underside. Adult Broad-shelled turtles may weigh 4 to 5 kilograms and live only in permanent, deep water. The female Broad-shelled turtle nests in autumn, after the eggs of the other turtle species have hatched. This species nest up to 500 m from the water and development of the embryo can be delayed in response to unfavourable environmental conditions such as low rainfall. This delay can lead to an incubation period of 1 year or more. Broad-shelled turtles feed mostly on fast swimming prey such as fish and shrimps, they will also eat dead animals and are sometimes caught and drowned in baited traps targeting other animals.

The third turtle species found in the Murrumbidgee catchment is the Macquarie River turtle (Emydura macquarii) and, its short neck distinguishes it from the other two long-necked species. These are part of the genus Emydura, they are about the size of a dinner plate and like to bask on logs. Unlike the Eastern long-necked turtles, they are rarely seen on land. They do however come on to land to nest during November. Eggs can take 6-8 weeks to hatch and some females lay two clutches of eggs in one season with a clutch size of up to 30 eggs. Short-necked turtles are omnivorous, eating plant material and invertebrates. They also help to clean up dead fish and other carrion.

Turtles are monitored in the Murrumbidgee Selected Area as part of the fish surveys. Large fyke nets are set in wetlands and creek systems overnight at long-term monitoring sites. They are set in a way that any turtle or other air breathing aquatic animals (frog or Rakali) that go into the net will have adequate access to oxygen with a portion of the net on which to rest is out of water preventing drownings from occurring.

Figure 6 Adult (left) and juvenile (right) Macquarie River turtle detected in the Lower Murrumbidgee and Yanco Creek system. Note the short neck and white stripe down the side of the face. Photo credit: Anna Turner.

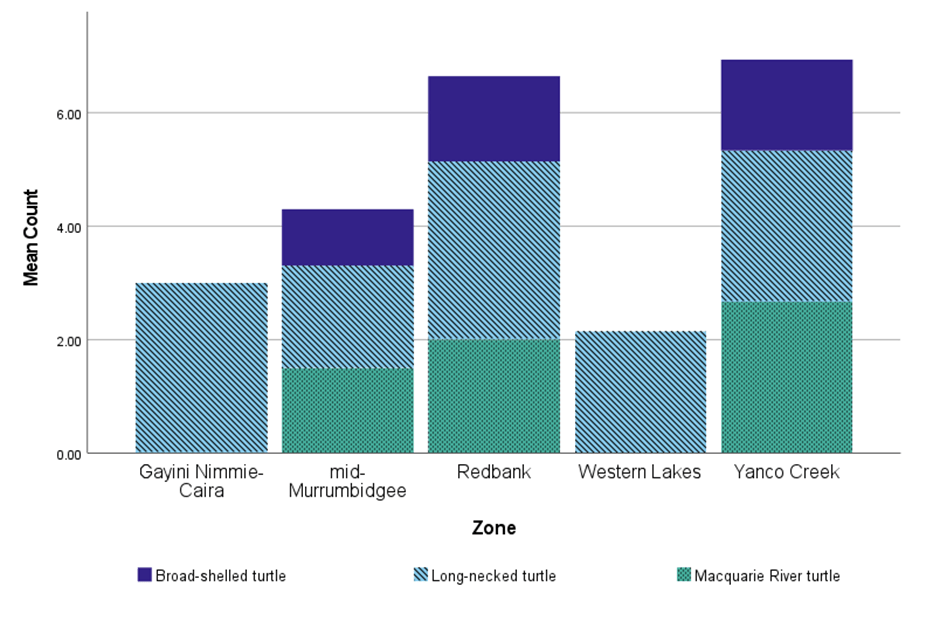

From the 2014-15 water year to the 2022-23 water year, Eastern long-necked turtles made up 67% of all turtle captures, 19% were Broad-shelled turtles and 14% Macquarie River turtles. Turtles are long-lived animals and breeding success is influenced to some extent by food availability in the wetland during the preceding years, as well as fox predation. During the 2022-23 water year, all three species were detected in the mid-Murrumbidgee, Redbank and Yanco Creek zones with the highest mean count detected in the Yanco Creek (Figure 7). Threat to turtles include vehicle strike, and wetlands drying out and stranding juveniles before they are able to move. In some areas, foxes can take up to 90% of all eggs.

During the 2022-23 survey period, a broad range of age cohorts of all three turtle species were detected. Individuals ranged from carapace length of 290 mm down to 70 mm. Two of the 65 Eastern long-necked turtles captured in 2022-23 were considered juveniles. Broad-shelled turtles ranged from 372 mm down to 99 mm with three of the 14 considered juveniles. A total of 16 Macquarie River turtles were detected and they ranged from 322 mm down to 110 mm, with four considered juveniles.

The natural flood event which occurred in 2022-23 led to reconnection of a number of key wetland sites to the main river channel. This increases transfer of nutrients between the two environments, providing food and habitat for many species. Refuge wetland sites which received Commonwealth water for the environment in the mid- and Lower Murrumbidgee are observed to support a higher diversity of turtle species compared to non-permanent wetland sites. These key wetland sites include Gooragool, Yarradda and Waugorah Lagoons.

During September the Murrumbidgee MER team were joined by Jamie Woods (Nari Nari Land Manager at Gayini Nimmie-Caira), and his sons Bronx and Oaken, down at Bayil Creek to conduct fish and turtle monitoring. Together they measured eight Eastern long-necked turtles which had been caught overnight at the site.

For more information about turtles in your area, check out www.1millionturtles.com to learn more about how the 1 Million Turtles program is helping to increase survival rates of freshwater turtles and turtle nests, increase knowledge of freshwater turtle distributions across Australia and train community in methods that promote turtle conservation.

The Murrumbidgee is a lowland river system with large meandering channels, wetlands, lakes, swamps and creek lines. Our work here focuses on understanding how native fish, waterbirds, reptiles and amphibians, as well as wetland vegetation communities, benefit from these targeted environmental watering actions.

The information on this website is presented by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the Department) for the purposes of disseminating information to the public. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice.

The views and opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Portfolio Ministers for the Department or indicate a commitment to a particular course of action.

While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this website are factually correct, the Commonwealth of Australia does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of its contents. The Department disclaims liability, to the extent permitted by law, for any liabilities, losses, damages and costs arising from any reliance on the contents of this website. You should seek legal or other professional advice in relation to your specific circumstances.

Use of this website is at a user’s own risk and the Department accepts no responsibility for any interference, loss, damage or disruption to your computer system which arises in connection with your use of this website or any linked website.